How the Trans-Siberian railway became the love train | Life and style

The Trans-Siberian railway, the greatest train journey in the world, is where our love story began.

When I booked a ticket on the Rossiya train to travel from west to east through different time zones, I expected a great adventure, to rub shoulders with people from a very different culture and to try out the small bit of Russian I had diligently studied.

Never did I expect to meet the love of my life and say “I do†by the time the train skirted around the far edges of Lake Baikal and out of the city of Irkutsk in Siberia.

Ours was a holiday romance like no other; love kindled on that great iron road put in place at the time of the tsar and which tracks across the former Soviet Union week in, week out. Over four days as the train trundled its way through the heart of Russia and in to Mongolia, two people who were adamant they were not looking for love, opened their hearts, fell madly in love, began planning a future, pledging to spend the rest of their lives together.

It was the late 1980s, the era of glasnost and Gorbachev. I had stocked up on notebooks and pens to write a journal of my travels, and Tolstoy was stuffed in my rucksack for some light reading. John had packed notebooks and pens to sketch moments of his journey. But all these lofty notions were forgotten as we got to know each other and love blossomed.

The two of us, an Irishwoman and an Englishman, were travelling to China out of Moscow, a journey of 7,854km. John had caught my eye early on, tall with round John Lennon glasses and a leather jacket hanging over one shoulder. He was in the compartment beside mine; we first chatted as we stood in the corridor on a sweltering July day, the window down, the warm air rushing past us as the train made its way out of the gloomy industrial suburbs of Moscow; the grey city receding, the land folding away farther than the eye could see. Outside Moscow, picket-fenced dachas, the summer houses of the rich Muscovites, dotted the landscape before giving way to countryside and forest, thousands of miles before we reached Irkutsk in a journey that would take in big and small stations, all busy no matter the time of day or night.

To understand this great railway journey and enjoy it at its best, it is necessary to drop down a few gears and watch the world go by. The world on the train goes on at its own pace as it devours the railway miles, silver birch trees standing sentry along the line. The compartments in the carriage are small, so during the day as all the other passengers sit comfortably, it is easier to take up residence on the corridor pull-down seats by the windows. People stop and chat passing back and forth to the toilet or the samovar, where hot water is dispensed night and day.

Time is irrelevant. The train does its business on Moscow time, the local stations on local time in different time zones. For the traveller, the only constant is the gentle roll of the train, the background piped rock music; the car attendants, or provodnitsa, patrolling the carriage sweeping and tidying.

Sitting side by side, there was plenty of time to talk, and that was exactly what John and I did, getting to know each other, finding out how much we had in common. The fact that John was 18 years older than me was irrelevant â€" when we were together it was as if we were on a specially chartered private train, we noticed nobody else.

We soon became the talk of the train, the carriage attendants sending updates to colleagues, and gleefully telling our story to the babushkas selling wares when we stopped at stations. The Trans-Siberian had become the love train. Some of the old women in their flowery housecoats, scarves knotted tightly under their chins, pushed free sweets on us, giggling and laughing, throwing their eyes to heaven. Others shook their heads, wagged their fingers and predicted it would not last beyond the next long stop.

At Novosibirsk, as the train pulled in to the platform late at night, we first talked of the future. Of moving countries to be together. I wanted to send a message back along the line to the doubting babushkas. For many it must have looked like a holiday fling, but we knew this was only the beginning.

Thousands of miles down the line, we both knew we weren’t just on a trip of a lifetime, but a life-changing journey. We realised when the train finally reached its destination that we wanted to continue on new adventures together.

For me, the realisation we were meant to be together came soon after the train stopped at Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg station) and John, a huge train buff, noticed that a railway sign saying post or mail in Cyrillic had fallen under our train and on to the tracks. He was tempted to reach down and grab it, but decided to leave it. So IÂ hunkered down and pushed my hand under the train, just as we were called back on board. I hid the sign under my jacket, and John did not even know IÂ had it until we got back in to the carriage. He knew he was certain when he saw me hanging out of the window to get a photograph of the train coming down the opposite line. He pulled me in just in time as the train rushed past, his face white, mine triumphant saying I had got the shot. He says he knew then it was never going to be boring with me and I knew I could always trust him to have my back.

Irkutsk was our first stopover after 5,000km. It was here on the shores of Lake Baikal that John asked me to marry him. The air was clear, the lake water lapping on the shore, the early morning sunshine burning off the mist curling across the water. I needed no time to think it through and accepted his great-aunt’s gold ring-keeper on my left hand as an engagement ring.

We continued on our journey across Mongolia, China and on to Hong Kong. When I rang my mother and told her I was going to marry a man I met on the Trans-Siberian railway she let out a big sigh. “Why are you marrying a Russian? Does he even speak English?â€

The Trans-Siberian railway transformed the heart of Russia when it was built. Travelling thousands of miles on this great railway changed our lives for ever. Twenty nine years later, we can say we are all the better for it.

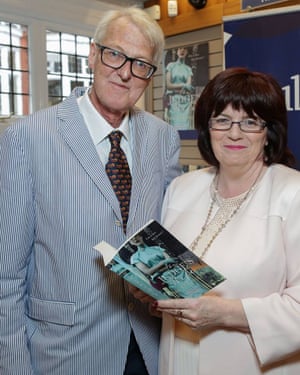

• The Ludlow Ladies’ Society by Ann O’Loughlin (B&W Publishing, £12.99). To order a copy for £11.40, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.

0 Response to "How the Trans-Siberian railway became the love train | Life and style"

Posting Komentar