'It's digital colonialism': how Facebook's free internet service has failed its users | Technology

Free Basics, Facebook’s free, limited internet service for developing markets, is neither serving local needs nor achieving its objective of bringing people online for the first time.

That’s according to research by citizen media and activist group Global Voices, published this week, which examined the Free Basics service in six different markets â€" Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, Mexico, Pakistan and Philippines â€" to see whether it was serving the intended audience.

Free Basics is a Facebook-developed mobile app that gives users access to a small selection of data-light websites and services. The websites are stripped of photos and videos and can be browsed without paying for mobile data.

Facebook sees this as an “on-ramp†to using the open internet: by introducing people to a taster of the internet, they will see the value in paying for data, which in turn brings more people online and can help improve their lives.

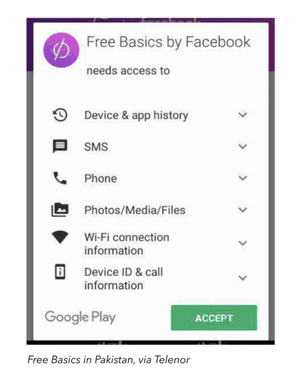

However, the Global Voices report identifies a number of weaknesses in the service, including not adequately serving the linguistic needs of local populations; featuring a glut of third-party services from private companies in the US; harvesting huge amounts of metadata about users and violating the principles of net neutrality.

“Facebook is not introducing people to open internet where you can learn, create and build things,†said Ellery Biddle, advocacy director of Global Voices. “It’s building this little web that turns the user into a mostly passive consumer of mostly western corporate content. That’s digital colonialism.â€

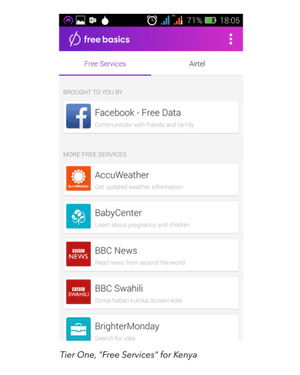

To deliver the service, which is now active in 65 countries, Facebook partners with local mobile operators. Mobile operators agree to “zero-rate†the data consumed by the app, making it free, while Facebook does the technical heavy lifting to ensure that they can do this as cheaply as possible. Each version is localized, offering a slightly different set of up to 150 sites and services.

But many of the services with the most prominent placement â€" on the app’s homepage - are created by private US companies, regardless of the market. These include AccuWeather, Johnson & Johnson-owned BabyCenter, BBC News, ESPN and the search engine Bing. There are no other social networking sites apart from Facebook and no email provider.

Alongside them are country-specific offerings, but their presence is determined by which companies have adapted their code to meet the requirements of the Free Basics platform, rather than those that meet local needs.

“The content does not include some of the important websites Ghanaians want to look at,†said Kofi Yeboah, who researched the app in Ghana, noting that popular news websites such as MyJoyOnline and CityFM were missing.

In the Mexican version of the app, offered by Telcel, there’s only one local site on the first page: for the foundation of the billionaire Carlos Slim, the CEO of Telcel. Bizarrely, the same app also offers two Nigerian websites and a regional news outlet for Argentina.

Free Basics is also restricted in terms of language. Kenyan users can choose an interface in English or Kiswahili, but most of the services are offered in English only. In Ghana, everything is in English, even though other languages, such as Twi and Hausa, are widely spoken.

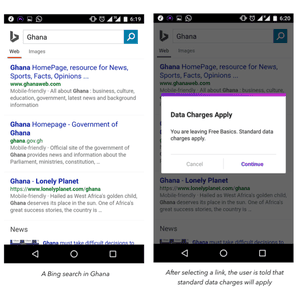

When a user tries to access information outside of the tiny walled garden, a pop-up appears urging them to buy more data. For example, although Free Basics includes access to the Bing search engine and will show snippets of listings for free, reading any of the results of the search requires payment. On Facebook, this means people can see links to news and blogposts but can’t read them.

“This means people are reacting to articles through clickbait headlines only and not by reading the whole article. It makes it difficult to detect fake news,†said Mong Palatino, who studied the Philippines version.

This is particularly jarring given the way that Free Basics as advertised.

“The advertising implies that it’s free internet, but then you actually use it and it’s not really the full internet,†said Palatino. “It misleads the public and makes them think these sites and services are the essential tools.â€

The promotion of certain sites and services through zero-rating the data also infringes on net neutrality, the idea that internet service providers (ISPs) should treat everyone’s data equally to prevent a tiered system, in which some content providers have an unfair advantage.

It was these concerns, along with accusations of cultural imperialism, that scuppered the Free Basics launch in India (a move that led the Facebook board member Marc Andreessen to angrily tweet remarks that implied support for British colonialism).

Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, has argued that some internet is better than no internet.

“Arguments about net neutrality shouldn’t be used to prevent the most disadvantaged people in society from gaining access or to deprive people of opportunity,†he said on his Facebook profile in 2015.

It’s an argument that doesn’t wash with the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Gennie Gebhart: “Facebook’s efforts to bring the internet and more choice to people are laudable, but it’s unclear if that’s truly its goal. Facebook has a responsibility to its investors and that is being served by getting more eyeballs on its site, to lure users.â€

Whatever Facebook’s true goal, Free Basics offers the company another treasure trove of data: all user activities within the app are channeled through Facebook’s servers. This means Facebook can tell which third-party sites users are looking at, when and for how long.

“The program has created substantial new avenues for Facebook to gather data about the habits and interests of users in countries where they aspire to have a strong presence, as more users come online,†said Global Voices.

In spite of its shortcomings, Free Basics has grown rapidly and, according to Facebook, is used by 50m people. However, it’s mostly used by people who want to extend their mobile data package for free as opposed to connecting those who previously didn’t have access to the internet â€" an audience Facebook has repeatedly stated it is trying to reach.

“It is not a great approach for bringing people online, but it’s really good at saving costs for people already online,†said Dhanaraj Thakur, of the Alliance for Affordable Internet.

“The narrative Facebook is concerned with is about increasing access, but there’s a lack of empirical evidence. But that’s the whole point of the project!â€

Facebook refused to answer questions about how many people it had brought online for the first time, how it places content within the apps or how the company measures the success of the scheme. However, the company pointed out the report only looked at a few markets and that it is an open platform for which any content provider can adapt their services.

“Working with partners and developers on Free Basics, we’re helping people around the world access impactful local services, including health resources, education and business tools, refugee assistance sites, and more,†said a spokeswoman.

Thakur believes a better solution would be to give low-income groups a limited amount of free data to access the open web.

Even so, the cost of data is one of many problems that need solving to get the unconnected online, said Gebhart.

“The barriers to internet access include signal availability, device ownership, education, digital literacy and electricity â€" these are arguably far more elemental and urgent,†she said.

0 Response to "'It's digital colonialism': how Facebook's free internet service has failed its users | Technology"

Posting Komentar