Radio Erena: a beacon of hope for Eritrea | World news

Ten years ago, Biniam Simon, a journalist at Eri-TV, Eritrea’s state television channel, was informed by his government overlords that he would, after all, be allowed to travel to Japan to attend a seminar on video production. This, to put it mildly, was surprising. Those who leave Eritrea, a single party state with one of the worst human rights records in the world, usually do so only by clandestine and extremely risky means. But if Simon was astonished, he was also realistic. “They only allowed me to go because they thought there was no way to escape from Japan,†he says. “Japan had agreed I would be returned to Eritrea.†Knowing this, he didn’t allow himself even to toy with the idea of defection. He made no plans. He dreamed no dreams. He hoped only to enjoy a few peaceful days outside the prison of his homeland.

Once he was in Japan, however, everything changed. “Something happened, in my section of Eri-TV,†he says. “A lot of people went to prison. Passwords and email addresses were asked for. Someone tipped me off, and I decided not to go back.†This wasn’t an easy decision. The parents and siblings he was leaving behind would, he knew, pay the price in the form of harassment, or worse, on the part of the government. But no sooner had he taken it than he understood its inevitability.

“At some point, you have to make it,†he says. “[In my job], I was reporting for the president’s office â€" the meetings of cabinet ministers, and so on â€" and the more high-profile you become in Eritrea, the more danger you’re in. Make even a technical mistake, and you will be punished. One way or another, I knew I would end up in prison eventually.†In Eritrea’s prisons, makeshift and overcrowded, detention periods are arbitrary; torture and judicial executions come pretty much as standard.

Japan duly refused Simon asylum. But with the help of the French NGO Reporters Without Borders, he made it to Paris, where he has lived ever since. His new life was difficult at first. He knew no one, and spoke not a word of French. He worried constantly about his family who, as predicted, were soon called to explain themselves to the administration. But he also had a plan, and this kept him going. He wanted to set up a radio station, one that would broadcast not only to the sizable Eritrean diaspora in Europe â€" some 5,000 people leave the country illegally every month â€" but also, more daringly, to the population of Eritrea itself.

“I started thinking about it immediately. You have to understand: Eritrea is completely closed. No information is available there at all, about the outside world or what is going on internally. So if you’re an Eritrean journalist, and you make it to a place where so much information is available, the first thing you think is: why not tell people all this? It was the obvious thing to do.â€

Simon, who has the slightly distracted air of the true workaholic, took his idea to Reporters Without Borders, and with its support and some funding, he started trying to recruit his first collaborators, a process that was challenging even in Europe, where he began: of the 60 Eritrean journalists who had made it to the continent, most remained too afraid of the government and too worried for their families to work with him at first.

They also struggled to understand the idea of independent journalism: “They thought that you either worked for the government, doing its propaganda, or that you worked for the opposition. They didn’t understand that we just wanted to give people the information, and what they would do with it afterwards would be up to them.â€

Still, their reluctance was as nothing compared to the difficulties involved in getting stories out of a country that for almost a decade has sat in bottom place in the Index of World Press Freedom (now only North Korea ranks lower). How would it be done? In the capital, Asmara, the government’s network of informants is so extensive, many people are unwilling to talk politics even with members of their own family.

In the end, most of the diaspora journalists agreed either to use pseudonyms, or to have their stories recorded by someone else. Meanwhile, Simon slowly built up a network of contacts inside Eritrea. Eight years on, and the majority of Radio Erena’s sources in the country are, he says, ordinary people who report with their eyes and ears, sending out tiny but invaluable bits of information almost every day; the remainder work inside government ministries, or, more rarely, on the ground as journalists. In order to protect them, he and his colleagues in Paris â€" there are now five staff â€" never share the names of their contacts with one other, and they each use a different system to communicate with their sources: Simon, for instance, uses code to talk to his.

“I don’t know my colleagues’ sources, and they don’t know mine,†he says. This system also helps with the verification of stories: “A colleague can ask his source if he can confirm something my source has heard, and because they don’t know each other, we have a clearer idea of whether it’s likely to be true.†Stories must have three separate sources, no matter how long this might take: “Information can be 10 days old, depending on the electricity supply in Eritrea and the availability of internet. But it is better to wait, and be 100% sure that what you are broadcasting is correct, than to put out rumours. Because if you make a mistake, you may have fallen into a propaganda trap laid by the government.â€

The station broadcasts a two-hour programme in Arabic and Tigrinya seven days a week, repeating it several times a day, giving listeners inside Eritrea multiple opportunities to listen (they may do so, in the privacy of their own homes with the shutters closed and the sound turned down, only when electricity is available â€" which it often isn’t). As well as news about what the regime may be up to, it provides a detailed picture of what is happening to the refugees who are travelling to Europe â€" when a boat carrying 360 Eritreans capsized off Lampedusa in 2013, a correspondent was immediately dispatched to Italy â€" as well as features about diaspora success stories, footballers and athletes among them.

It runs smoothly. There is always a lot to tell. Making sure it can be picked up in Eritrea, however, remains a constant struggle. In 2012, the government managed to block it â€" seemingly unbothered by the fact that in doing so, it also blocked its own television channel (both broadcast on one satellite frequency). It has also successfully jammed it on shortwave, and on at least one occasion has hacked into the Radio Erena website, destroying it completely. “It’s a nonstop challenge,†he says. “We’re constantly fighting them, and it’s getting harder and harder because they are now employing new experts from China and Indonesia.â€

But if this is exhausting, it’s also hugely encouraging: “It means that what we’re doing is working. We know this because the government wants us to stop.†In the early days of Radio Erena, there were reports of listeners being sent to prison. The state made an example of people, to discourage others. Now, though, it seems to have accepted that if it wants to close Erena down, it needs to attack the station itself rather than its listeners. Quite simply, they have become too numerous. For obvious reasons, no official listening figures for Radio Erena are available. But when Simon and his colleagues ask new arrivals in Europe how many people back at home are tuning in, the reply is always the same. “You can’t imagine how important it is,†they’ll tell him. “It’s the only thing that gives anyone any hope.â€

Radio Erena broadcasts from two small rooms on a sleepy Paris backstreet â€" downstairs is the office; upstairs is the studio, a tiny kitchen and a bathroom â€" the walls of which are decorated with old, sun-drenched posters that advertise, in happier times, the country’s delights for tourists. “Massawa: Pearl of the Red Sea†says one. Another shows off gleaming Asmara, whose well preserved modernist Italian architecture, built after Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, won the city its listing as a Unesco world heritage site earlier this month. Ask Simon and the others what Eritrea is like, and it’s to these images that they instinctively turn.

“Oh, it’s lovely,†says Fathi Osman, another Erena journalist. “Asmara is more than 2,000 metres above sea level, and the climate is temperate all year round.†He stretches an open palm in the direction of the relevant poster, a gesture that is at once both sweetly proud (come visit!) and unbearably sad (but you never will, and nor can I, for the time being).

Yes, but what’s it really like? They struggle to find the words. “I cannot explain it,†says Simon. “It’s a zombie place. You wake up, you go to the job to which you have been assigned, and then you go back home, and repeat. You cannot lead the life you want to. There are no breaks, no vacations, no social life. It’s really boring. Boredom and fear: a bad combination.â€

The mostly young people who slip over the border into Ethiopia or Sudan are risking everything: from there, assuming they avoid being shot by border guards, they will either make the long and arduous journey overland to Libya, from where they hope to reach Europe by sea, or they will travel across the lawless Sinai desert to Israel, where more than 30,000 Eritreans currently reside. But still they do it. According to the UN Refugee Agency, in 2014/2015 Eritreans represented the largest number of asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean.

“They will say: at least you know when you are dead,†says Osman. “They think even that must be better than life in Eritrea, which is a kind of half-life, a living death.â€

Like Simon, Osman, a former diplomat, first left Eritrea with official dispensation, having been posted to Saudi Arabia. His situation, however, was more complicated. His wife and children remained in Asmara: the Eritrean government, primed for defections, requires all diplomatic families to stay at home, seeing them as a kind of emotional collateral. But then his son fell seriously ill. Could his wife now join him in Saudi, so the child could be treated in hospital there? (In Eritrea, there is a severe shortage of doctors.) At first, permission was refused. Then it was given, but only for his wife and the sick boy. When he told the authorities the other children could not be left alone, he did so without any expectation that they would change their mind. To his amazement, though, they did. “My son’s illness was a blessing in disguise,†he says, quietly. This was his moment. In 2012, he left for France, leaving his family in hiding in Saudi Arabia. It was two years before he saw them again, their papers having finally been arranged.

Osman, a gentle-seeming, slow-moving man with a serious coffee habit, is the author of From the Dream of Liberation to the Nightmare of Dictatorship, a book (written in Arabic) in which he attempts to trace the roots of Eritrea’s descent into totalitarianism. “I wanted to answer the question: how did all our hope and inspiration end up here?†he says.

In his mind, Eritrea’s liberation from Ethiopia, the country from which it finally won independence in 1993, and its subsequent authoritarianism are inextricably linked. “Eritrea, a small country, achieved one of the most formidable victories in the history of the world,†he says. “We defeated Ethiopia, an African superpower. We crushed it! But in this very victory the seeds of dictatorship were planted. Now, there was a community of fighters who believed they could do anything, without help from any other country. We absorbed the mindset of the militarists entirely. We ended up fighting everyone. The gun has been everything ever since.â€

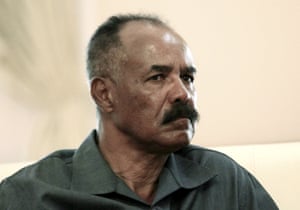

It was 71-year old Isaias Afwerki, the president since 1991, who led the country to victory against Ethiopia, after a war lasting 30 years. As the leader of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, he promised not only hope and autonomy, but elections, too. These never came. The EPLF was renamed the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, and it is now Eritrea’s only legal political party. All other political activity is banned; the country is estimated to have at least 10,000 political prisoners. Dissent is increasingly rare.

In 2001, a group of Afwerki’s closest associates, unsettled by the sparking of another border dispute with Ethiopia â€" relations between the two countries continue to be extremely tense â€" confronted the president, accusing him of mishandling the latest conflict; and in 2013, a group of soldiers took over the HQ of Eri-TV, calling for the release of political prisoners and the implementation of the constitution. But on both occasions, those involved were swiftly rounded up and imprisoned. The opposition is now restricted to an organisation known as Freedom Friday, which quietly puts up posters and scrawls political graffiti on banknotes. “It really takes the form of the 5,000 people who leave every month,†says Osman. “They’re the opposition.†Eritrea, which has a population of 6 million, is one of the fastest-emptying nations in the world. The diaspora is now half a million strong.

Afwerki’s oft-stated raison d’etre is the survival of his young country, which he regards as being eternally under threat â€" not at war, but never at peace either â€" and it is one that the people took at face value at first. “What makes him different from other dictators is that his lifestyle is not lavish,†says Simon. “He wants to look like one of the people, a working-class man, and in the beginning, we thought he and the others would make Eritrea great. People worked for free, including me: I did for two years. Everyone did, to build the country.†In this sense, the population’s eyes were wide open. “We saw what was happening. I can say that everyone did. But it was a new government, and those in power had no experience of civilian office, so when they made mistakes, we said: ‘OK, it’s not a big deal. They’re learning. Things will get better.’†By the time people were prepared to admit to themselves and each other that things were not getting better , it was too late to say so out loud.

Most asylum seekers cite conscription into the army as their primary reason for leaving Eritrea. In 2002, the statutory requirement of 18 months of military service for men and women â€" a period that begins when students are in the last year of their secondary education â€" was extended to become, in practice, indefinite, with the result that many people now serve well into their 50s. A UN commission has called the Eritrean army “an institution where slavery practices are routineâ€. The pay is minimal (around £30 a month), leave is rarely given, and conscripts remain away from home for years at a time.

Soldiers are also subject to torture, sexual torture, arbitrary detention and forced labour. The country’s mining industry is, for instance, serviced by military personnel. Conscripts also clean the streets. In effect, the entire country is a vast military camp.

In the face of such misery, how may the Eritrean people comfort themselves? Not by practising their religion, that’s for sure. The government is reported to persecute “suspect†Muslims â€" a term that may extend both to those it regards as extremists, and to non-Sunnis â€" and the Christian denominations it does not officially sanction. Some 3,000 Christians are currently imprisoned in the country (around 200 were reportedly arrested this month alone, including 20 children). The Eritrean Orthodox Church is recognised, but Abune Antonios, its 89-year-old patriarch, who was deposed by the government in 2007 after he demanded the release of imprisoned Christians, has been under house arrest for the past 10 years.

Even family life is less of a balm than it might be. People are reportedly not permitted to meet in groups larger than two, and travel permits are required to move around the country. Thanks to conscription, every family is always missing someone, and those left behind struggle to make ends meet, particularly in agricultural communities, where labour is so vital.

Above all, people are afraid to talk freely â€" and so it is that the bonds weaken, and sometimes break. Simon speaks to his mother only rarely. What is there to say? “You have to be so careful,†he tells me. “Sometimes, I can’t see the point of calling at all.â€

Do he and Osman have it in them to feel hopeful about Eritrea’s future?

“If you don’t have hope, you’re dead,†says Simon. “Nothing is for ever.†But he doesn’t look hopeful, and as he readily admits, even if the regime were to fall, worse could follow.

“There is no working parliament, no vice president and no organised opposition. When the president goes, there will be… chaos.†Is the current government susceptible to pressure from outside? Osman believes not: “He [Afwerki] regards the rest of the world with disdain.â€

In 2009, when the president was asked by a Swedish TV channel about Dawit Isaak, the Swedish-Eritrean journalist who has been imprisoned without trial since 2001, his reply was chilling. “We will not have any trial and we will not free him,†he said. “We know how to handle his kind.†He added that he regarded the position of Sweden on this matter as “irrelevantâ€.

All they can do, then, is to continue their work at Radio Erena. In the beginning, the challenge was to get people to listen. Then it was to get them to discuss what they heard. Now, they would like to expand their coverage, by hiring journalists in other north African countries.

“If something happens to your neighbour, it will affect you,†says Simon. “Eritrea is already involved in the conflict in Yemen [where its forces are fighting on behalf of the Arab coalition].†To those who say journalism no longer matters, here it is, mattering very much indeed.

Are they homesick? Yes, though this isn’t a straightforward thing, particularly for Simon.

“I don’t live in France,†he says, with a low laugh. “Physically, I am here, of course. But I live in Eritrea. I wake up and I come here and I stay late, and then I go home and sleep. That’s all. All day long, I’m with Eritreans, talking about Eritrea.â€

It is what he needs to do, but it doesn’t make him any happier. Life is lived in limbo nevertheless. “Sometimes, I feel sad. I want to see places, to take pictures with a camera. But the furthest I go is the coffee shop at the end of the street.â€

The UK charity One World Media presented its 2017 special award to Radio Erena last month

0 Response to "Radio Erena: a beacon of hope for Eritrea | World news"

Posting Komentar