The final bar? How gentrification threatens America's music cities | Cities

At a Sixth Street bar in the heart of Austin, Texas a pop up version of Seb’s jazz club from the Hollywood hit film La La Land is being set up â€" its blue letters yet to be switched on. Nearby, a replica of Breaking Bad’s Los Pollos Hermanos fast food restaurant has appeared, causing a minor Twitter frenzy.

These are just two of the attractions materialising in the city in time for the music and media festival South by Southwest (SXSW), and throughout the 10 days of the event it is hard to find someone who isn’t wearing an official SXSW wristband worth $1,000.

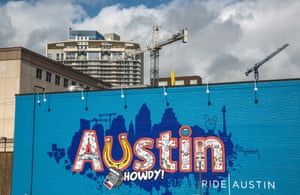

What started 30 years ago as a celebration of Austin’s local music scene, though, is now in danger of harming the very thing that made it unique. SXSW brings in hundreds of artists from around the world, 200,000 visitors and $325.3m (£250m) to the city’s economy. Its success has helped Austin establish music as a fundamental part of its development, but at the same time, as many as 20% of musicians in this self-appointed “live music capital of the world†survive below the federal poverty line.

According to a recent study by the Urban Land Institute, the city is “in the effective ‘11th hour’ of the endangerment of the live music sceneâ€, brought on by Austin’s rapid growth â€" it is now the fastest growing city in the US in terms of population, jobs and economy.

It’s a difficult reality for the city to confront. Austin is one of the three major US “music citiesâ€, alongside New Orleans and Nashville, that have capitalised on this local culture at the risk of ruining the scenes that made them famous in the first place. In Austin, the local live music scene is now paying the price for its success. Brian Block, of the city’s economic development office, says despite an apparent city-wide financial boom, local musicians’ income is “at best stagnating, and possibly decliningâ€.

Hayes Carll, a 41-year-old Grammy-nominated artist who recently won Austin’s Musician of the Year, says that for most Texans, Austin is “the mecca of music citiesâ€. It was where it “all came together: the songs, the record stores, the community, the identity. It was the first place I went where I could say I’m a singer-songwriter and they didn’t ask me what my real job was.â€

Music lives throughout Austin’s 200 or so venues, the annual music awards and festivals, and the many brilliant artists including Townes Van Zandt and Janis Joplin who have called it home. It was where Willie Nelson allegedly reunited the hippies and rednecks when he first went on stage at the Armadillo World Headquarters in August 1972. Today, Austin’s love of local creativity is immortalised in folk singer Daniel Johnston’s “Hi, how are you?†mural, depicting his iconic alien frog near the city’s university.

But despite this rich history, long-standing venues in Austin’s downtown Red River District are being forced to adjust to an influx of new neighbours â€" mostly expensive condos or hotels. Rising rents have forced venues like Holy Mountain and Red 7 to close, while noise complaints are an ongoing problem â€" hotels offer earplugs for a better night’s sleep.

“There’re some less than wonderful aspects to the growth process, and I know a lot of friends who have had to leave Austin,†says Carll, a Texan who has lived here for 12 years. “Austin is going to have to fight to keep some of the things that made it special â€" like the affordability and how you could be yourself and do whatever you wanted. When you become the hot cool city that everybody’s moving to, some of that freedom can get pushed out.â€

The city government is keen to stress that they’re working to preserve the live music scene. In 2013 the Red River District was given its “cultural†title to highlight its local significance. Block says they are now implementing a Red River extended hours pilot programme in the hope that an extra hour of live music on the weekend will bring increased revenues to help cope with rising costs, and more paid work for the musicians.

The city is also revising its land development codes for the first time in 30 years in an effort to raise the profile of entertainment districts. There are other support systems that come from outside government too, such as Haam â€" which provides access to affordable healthcare for low-income musicians. “Music is very important to the culture, to the local economy â€" and I think it will remain so. Hopefully we can get ahead of the issues we know are coming,†Block says.

But some feel it’s too late. “I’m worried Austin will change negatively,†says Carll. “It’s great that Austin’s identity revolves around music, and that the city government is trying to do things to correct it. But none of that will matter if musicians can’t afford to live there, or the venues are shut down because of noise complaints, or you can’t get to the venue because you’re stuck in traffic on the highway.â€

New Orleans: music from cradle to grave

Across the state border in Louisiana, New Orleans is facing similar problems as it develops and gentrifies. There are fears that without local government actively supporting musicians, the scene’s survival could be at risk.

“How do you keep a [music scene] real and authentic and yet encourage people to get involved? It’s a paradox,†says Jan Ramsey, editor of local magazine OffBeat. “There’s an authenticity to the music and the people who make it, and the integration of black and white culture here â€" we never want to lose that.â€

John Swenson, journalist and author of New Atlantis, Musicians Battle for the Survival of New Orleans says the music “accompanies you from the cradle to the grave; it’s born out of the neighbourhoods†and permeates all levels of society. Jazz was born here, tracing back to the mixture of African drums and European horns played by slaves in the late 19th century; and part of its musical heritage is a long list of prodigious artists, from Louis Armstrong to James Booker.

This culture attracts some 10 million tourists to the city each year. But what is unique about it â€" and gives the scene greater strength â€" is how it has become an invaluable lifeline for the city’s regeneration after the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

In the Spotted Cat, one of the long-standing venues on Frenchmen Street, manager Cheryl Abana talks quietly as a jazz singer performs to a crowded room. “For a couple of years [after Katrina] it was pretty sad here and the music scene really helped out with trying to get everyone’s spirits up. It really helped build the city up again,†she says.

One of the most successful programmes to support the creative community following Katrina was Musicians’ Village, devised by Harry Connick Jr and Branford Marsalis alongside Habitat for Humanity. Situated in the Upper Ninth ward â€" one of the places hardest hit by the hurricane â€" it is a community of homes built by volunteers to support displaced musicians. “It’s a symbol to musicians that my community will be there when I get back; we’re going to keep that tradition alive,†says Jim Pate, executive director of the New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity.

A decade on, and artists of all genres and ages live in the village, including some of the godfathers of New Orleans heritage like Little Freddie King. “The musicians came back to New Orleans because music lived here,†says Swenson.

Nashville: the original music city

In Nashville, Tennessee, just a few blocks away from the famous honky tonk highway of Broadway, mayor Megan Barry sits in her office overlooking the state capitol. She is surrounded by motifs of Nashville’s music history: there’s a framed photograph of DeFord Bailey sitting on the steps of the Ryman auditorium, the first African American to perform at the Grand Ole Opry; and in the foyer hangs a painting by Chris Coleman of Kings of Leon. He gave it to Barry as a gift.

Music is everywhere. Although it has a heritage as influential as New Orleans, here it spreads further: from inside the mayor’s office and the government’s music council, to pretty much everyone you meet in the city who either plays it, writes it or listens to it (every taxi driver I meet is a musician; my Airbnb host is a songwriter).

As soon as I mention the phrase “music citiesâ€, Barry interrupts jovially: “Well, I think there’s only one!†Music has been part of Nashville’s foundations since the 1800s when it established itself as a centre for music publishing. Its heritage goes back to the Fisk Jubilee Singers who were based here â€" the African American a cappella band who were the first musical group to tour the world, raising money for freed slaves. Upon hearing them, Queen Victoria allegedly coined Nashville’s title as a “music cityâ€, which is now plastered across Tennessee billboards.

In 1925, WSM radio station was founded, which went on to broadcast the Grand Ole Opry â€" now the longest running radio show in the US that gave rise to some of the greatest names in country music. Music Row, the 200-acre area near downtown at its peak housed 270 music publishers, 120 record production agencies, 80 record manufacturing companies, 80 booking agencies and more. Elvis’ Heartbreak Hotel was recorded here at RCA in 1956; Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde was recorded nearby at Columbia Recording studios 10 years later.

Now, the $10bn industry music industry provides 56,000 jobs, supporting more than $3.2bn of labour income annually. “We can’t undersell its importance to our overall economic viability and continued growth and prosperity,†says Barry.

Nashville is projected to grow by 186,000 residents and 326,000 jobs in the next 25 years, and like Austin, has to confront uncomfortable growing pains in the form of gentrification. But music is firmly intertwined with the city’s municipal plans for how it will develop in the future.

The city provides affordable housing for musicians, and music programmes for school children, as “we know our graduation rates go up when kids are involved in music,†says Barry. “They go on and they have a career in music and then it feeds the job creation. It’s about feeding that pipeline.

“I think that although music evolves and changes, the ability for Nashville to grow and change with it has been part of our success.â€

At Dino’s bar in east Nashville, 26-year-old musician Cale Tyson is sipping on a beer. He is one of thousands of artists who moved here because of its history. “I feel like Nashville’s a town where musicians are treated really well. I don’t think anything’s closed off here,†says the Texan singer-songwriter. “In Nashville the competition and being around so many good artists forces you to work a lot harder.â€

People continue to migrate to Nashville because of this (about 100 a day), and this influx has inevitably changed the music scene â€" for better or worse. The country music capital of the world â€" which ignited the careers of Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn and Kitty Wells to name just a few â€" is now home to a burgeoning hip hop scene in the city’s so-called DIY clubs. Jack White moved in and set up a branch of Third Man records in 2009, while bands like Paramore, Kings of Leon and the Black Keys have all migrated here.

Nashville has even spawned a genre called “bro countryâ€, where burly men sing about chewing tobacco and celebrate being a redneck (with lyrics that repeat “red red red red redneckâ€), their odd rap verses a world away from the original country music that formed the soul of this city.

But the commercialisation of Nashville has led to accusations that country music is “deadâ€. A few years ago US country singer Collin Raye made a heartfelt plea for the city to get back to its roots and remember the musicians who “built and sustained the Nashville industry and truly made country music an American art form,†he said. “It needs to be that way once again. God Bless Hank Williams. God Bless George Jones.â€

And people are still trying to keep this alive. “I don’t think traditional country went away,†says Brendan Malone who runs a traditional honky tonk â€" an event celebrating country music â€" in the east of the city. “The fire was still kindling. It just needed to have some gasoline poured on it.â€

At Malone’s Honky Tonk Tuesdays, a man in a check shirt is barbecuing some ribs in the car park of the US army veteran’s club. Inside, ageing regulars sit at the bar nursing whiskeys to the sound of Hank Williams on the juke box.

In the main room, men and women of all ages wearing Stetsons and western shirts take turns two-stepping with each other as the band covers songs of Ernest Tubb and Red Foley. They perform against a backdrop of the US flag laid out in fairy lights.

There’s a sincere sense of pride in Nashville’s history here, despite how far the city and its culture has changed. With support from the mayor’s office to the local community, it seems Nashville took a bet on music and it paid off.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

0 Response to "The final bar? How gentrification threatens America's music cities | Cities"

Posting Komentar