Tracy-Ann Oberman: To my great-grandmother, Fiddler on the Roof was documentary | Life and style

As a child, when Tracy-Ann Oberman watched Fiddler on the Roof, her great-grandmother Annie would say, “This is like a documentary.†The village of Anatevka in the movie was just like the shtetl where she grew up. Her father had been brutally beaten in an anti-Jewish pogrom. She had fled to England to escape the violence.

Whenever Russia was mentioned â€" around the dinner table or in a news bulletin â€" Oberman’s great-grandmother would spit on the ground and say, “Whatever you do, don’t go there, they will behead you.†Then, slicing the air with her hand, Annie made a swishing noise as if the Cossacks were cutting off people’s heads.

Oberman tells me this in a quiet corner of a London bar. I am here to interview her about her forthcoming role in Fiddler on the Roof, in which she will play the part of Golde, the wife of the main character, Tevye. Then she tells me something extraordinary â€" she has never sung in a musical before.

So, how did she get the role? She says she heard that the director, Daniel Evans, was putting together a cast for Fiddler, and she let her agent know she was drawn to the character of Golde (but added, “I am not a singerâ€). Two days later she went to see Evans. She sang and he said he liked the timbre of her voice. Most of all, he saw that she was connected to the material. “You totally get Golde,†she recalls him saying.

Oberman is perhaps best known for her role as Chrissie Watts in EastEnders and in particular for the shocking episode in 2005 when more than 14 million people watched her kill her husband. She has also appeared in TV shows ranging from Doctor Who to Tracey Ullman’s Show, along with an array of theatrical and radio productions. Last year, she turned 50, but she gushes youth and energy. She speaks eloquently and with passion. At one moment she makes an earnest appeal for social justice, the next she shares a personal story with authentic emotion, and then she is goofing around.

She grew up in a Jewish immigrant family in Stanmore, north London. At a young age she became obsessed with her family’s past. After visiting the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Israel when she was four, her thirst for answers became “hard-wired†into her system. Yet neither of her parents were willing to provide answers. When she asked how many of her family members were murdered in the Holocaust (she says it could have been as many as 30), she was told, “We don’t know.â€

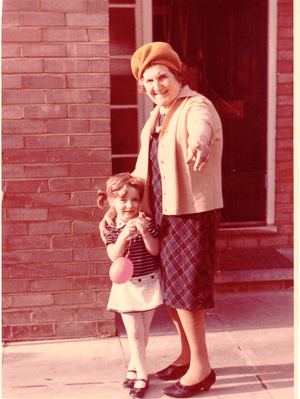

To fill in the gaps, she went to her great-grandmother Annie. Born in 1890, Annie lived with her family in a small shtetl near the city of Mogilev in Russia (today eastern Belarus). The village was located within the Pale of Settlement, the region of western Russia in which Jews were permitted to reside and work. Their life was hard. They were not allowed to own property, they could not be elected to the town council and schools restricted the number of Jews who could attend. In 1905, anti-Jewish pogroms swept the region, culminating in a wave of home-burnings, arrests, rapes and killings. This was when Annie’s parents sent her at the age of 14 to England, hoping for a better future.

On the boat to Liverpool, Annie met a young boy who had also grown up in a Russian shtetl. A little bit older and a little bit shorter than Annie, his name was Isaac â€" and he was a fighter. His family were socialists and protested against the tsar’s repression, which is why he had to leave. According to the family legend, Isaac fell in love with Annie on the boat and promised to find her in England, which he did, and they married, settled in east London and had a family. Those of Annie and Isaac’s family who stayed in Russia struggled on, many becoming Holocaust victims.

For years, Oberman struggled to be open about her Jewish identity. “There was a real shame about feeling persecuted,†she says. “It makes me want to cry even talking about this.†I ask if she has experienced antisemitism. She pauses a long time. Finally, she says she is nervous talking publicly about it. She might be misinterpreted; people might think of it as Jewish paranoia.

I tell her a story. In 1993, my German-Jewish grandmother, Elsie, took me and a cousin to Berlin, the city of her birth. Inspired by what we had seen, we asked if she thought we should change our name from Harding back to Hirschowitz. Elsie said no, that it would hurt our careers. Hirschowitz was too Jewish-sounding, we should keep our heads below the parapet, she said. That was the lesson she had learned from Hitler’s Germany. Recently, I tell Oberman, I have felt safe to come out publicly about my identity â€" writing books about my family’s Jewish background â€" and the experience has been rewarding, leaving me feeling more grounded, less anxious.

Apparently reassured, Oberman shares some of her experiences. There were a few difficult moments early in her career. The head of her drama school told her she should change her name from Oberman because it was too Jewish and she didn’t “look enough like Anne Frank†to be cast in Jewish roles. “I had a real dilemma about this,†she says. “Should I be called Tracy Denham? Tracy Holland? Then I thought, ‘Fuck it, I am who I am.’â€

She lists other negative experiences. A tutor who rubbed his fingers in a “monied way†when talking about Jews. Someone who told her she had to choose between being Jewish and an actor (“There’s room only for one religion in this business,†he said. “Christianityâ€). Signs she had seen in Hyde Park at an anti-Israel demonstration saying, “Hitler was right†and “Kill the Jewsâ€. All of this had led to her hiding her Jewish background.

The turning point, she says, had been the BBC show Goodness Gracious Me. She was friendly with two of its creators, Sanjeev Bhaskar and Anil Gupta. “They were so owning their heritage,†she says, “taking the mickey out of the older generation. It changed the concept of religious identity.â€

Do you own your Jewish identity now, I ask? “Yes, very much so,†she replies, adding that antisemitism is not as bad as it was, although she worries that antisemitism is now tied up with criticism of Israel. “The problem with antisemitism is that it is only the start. Next comes Islamophobia, sexism and homophobia,†she says. “It’s not just about me and my community, it is about a problem in society.â€

The conversation turns back to Fiddler on the Roof. We talk about the book it is based on, Tevye’s Daughters, written in 1905 by Sholem Aleichem (born Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich), the same year Oberman’s great-grandmother, Annie, fled Russia. There are differences between the book and the musical (which first appeared on Broadway in 1964 and then came to London in 1967 with Topol playing the part of Tevye). For instance, Golde dies in the book, adding a layer of grief and heartbreak that is absent from the musical. Similarly, at the end of the book, Golde’s husband Tevye is lost somewhere in eastern Europe, while in the musical the family is bound for the US. The original musical “was very much a love letter to Americaâ€, says Oberman, something that feels very different today given the current US president.

So, why did she decide to play Golde? “She is my great-grandmother,†she says, and adds that she admires the character as she keeps the family together â€" she is a survivor, fiercely loyal and, importantly for Oberman, is Tevye’s equal. “And the script is near perfect. The song and the book work hand in glove.â€

And then, warming to her theme, she embarks on a powerful riff. “Of course, it is very personal because it speaks so much to me, I am very close to the material. I also wanted to see it done away from shtetl shtick, I don’t want people to forget this is really about pogroms. It is very zeitgeisty, all about immigration and intolerance, about not feeling safe in the country of your birth and being thrown out and trying to find your identity.

“It is about community and traditions, and of the breaking of those traditions, where your children and grandchildren are brought up in a different country, having lost those traditions â€" and then who are you and what are you? This is the beauty and brilliance and universality of this story. You are only as strong as the community around you. It means a lot to me, for honouring the site-specificness of the story, for honouring my grandmother and for where we are in the world today. It moves me a lot.â€

Finally, she pauses for breath. “I think I talk too much,†she says. She looks at her watch, our time is up. She must get home to help her daughter (who is named after Annie) with her homework. Downstairs, Oberman pays for our drinks, we walk outside into the overripe evening air and say goodbye. It is one of those slightly awkward moments after an unexpectedly intense conversation â€" neither of us knows quite how to bring it to an end.

On the way home, I realise I have another question, so I text Oberman asking if I can call later. She tells me to try at 10pm that night, which I do. “So what is your question,†she asks with a trace of Golde humour. “Didn’t we cover everything earlier? Perhaps something political?â€

I tell her my follow-up, perhaps it is a little gauche, I say, but would she mind singing something for me from the musical? This is not what she was expecting. She says she really can’t, she would need the orchestration, it is too late at night, she has to put her daughter to bed.

Thinking I have offended her, or transgressed in some way â€" was it rude to ask a professional singer to perform over the telephone? â€" I apologise and try to close the conversation. “There is one line that is really powerful,†she says, ignoring my fumbling, “that always brings me tears. It’s from the song Anatevka. It comes towards the end of the musical.â€

There is a pause, and then she sings to me, down the phone. Her voice is soft, haunting, naked: “Soon I’ll be a stranger in a strange new place, searching for an old familiar face, from Anatevka.â€

And now I know why Oberman is performing in her first ever musical â€" she has found her voice.

• Fiddler on the Roof is at Chichester festival theatre, 10 July to 2 September; cft.org.uk.

Thomas Harding’s new book, Blood on the Page, will be published by William Heinemann on 31 August. @thomasharding

0 Response to "Tracy-Ann Oberman: To my great-grandmother, Fiddler on the Roof was documentary | Life and style"

Posting Komentar