The politics of fire: from Ancient Rome and San Francisco to Grenfell Tower | Cities

Flames were still visible inside the charred shell of Grenfell Tower when the backlash to the backlash began. “Too much political point-scoring going on about the Grenfell Tower tragedy,†complained one user on Twitter, hours after news of the devastating fire broke. “To politicise Grenfell is completely wrong,†added another. “Anyone trying to make political capital out of Grenfell should hang their heads in shame.â€

But politics, even in its narrow sense, is about governance and the distribution of power and resources within a community. Follow any of the threads behind the devastation at Grenfell, or those that have unspooled in its wake, and you tumble head-first into politics â€" raw, vital and fiercely contested. As David Lammy, the MP for Tottenham, observed: “If burning in your home is not political, I don’t know what is.â€

For as long as humans have built cities, those cities have been shaped by fires â€" and their manner, victims and aftermath have always been inextricably bound up with the political order of their day.

“Fire … is a highly political phenomenon,†explain the authors of Flammable Cities, an academic survey of urban conflagrations and the ways in which they have legitimised and strengthened power, as well as undermined it. “Fires can shape and alter the way a city is governed, and they can be utilised to play off one part of the population against another.â€

The political context of any fire starts with the systems put in place to prevent it, and the decisions regarding who, or what, is in most need of protection. The first large-scale fire-fighting force recorded was the Vigiles Urbani (city watchmen) of Ancient Rome, who were pressed into action during the Great Fire of 64AD â€" a disaster laden with political implications, from speculation over its cause (the Emperor Nero was widely rumoured to have ordered the torching of the capital himself) to debates over reconstruction in the city, two-thirds of which was destroyed by the blaze.

Over the centuries, different strategies aimed at avoiding urban fires have been used to entrench the autocratic nature of some regimes, or to showcase the supposedly enlightened and modernist credentials of others. In addition, the social background of those injured or displaced by fires has helped show the degree to which class, race and religion play a part in determining urban vulnerability.

“The fact that there isn’t a lot more discussion out there about the political history of urban fires is itself political,†says Greg Bankoff, a professor specialising in the history of disasters at the University of Hull. He points out that part of the problem stems from the fact that English, unlike many other languages, has only one common word for fire â€" which is used to mean both the chemical process of combustion and the act of devastation when a building or neighbourhood burns down. The former may appear natural or neutral, but the latter never is. In Arabic, for example, nar refers to fire in its basic form of warmth, heat or light, whereas hariq indicates a fire that is violent and causes destruction.

There is also a geographical divide at work between the global north, where urban fires are largely associated with the past, back when cities were largely fashioned out of wood, and the global south where fires continue to cause a huge loss of life today: an estimated 300,000 people a year die in fires worldwide, the majority of them in cities. “The lack of public awareness on this reflects the fact that most of those who dominate academic and policy-making circles live in western societies where the threat of fire has been largely reduced to a question of individual properties,†argues Bankoff. “But on a global scale, it’s mind-blowing.â€

The Grenfell blaze may have been confined to a single tower block, but like many of history’s great conflagrations, it has thrown the failures of the state into sharp relief and provoked a public interrogation of issues that stretch well beyond North Kensington. With it, the fire has unleashed a wave of grassroots community action, and has crystallised a set of national concerns over austerity, deregulation and lines of local democratic accountability. Whether or not it will prove to be a major catalyst for change at an institutional level remains to be seen.

One thing we can be sure of, though, is that this will not be the last time that urban fires spark crises in the political status quo. The combination of climate change and growing urbanisation is increasing the dangers of fire at the so-called wildland-urban interface â€" the zone between the edges of human development and unoccupied land. This is a particular problem in the United States, where an area amounting to twice the size of California has been deemed at high-risk of catching fire.

Meanwhile the rise in the numbers of displaced people across the planet â€" currently estimated at 66 million â€" is fuelling the spread of new urban spaces on the fringes of existing cities, often transient and informal, where the risk of conflagrations is highest.

Where those future fires take place, and what we do or don’t do to stop them, will say much about the political structures of our world, and could yet play a role in subverting them. “In many parts of the globe, fire may have receded from popular consciousness,†warns Bankoff. “In the years to come, that is going to change.â€

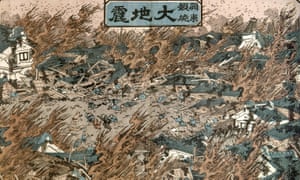

Edo (modern-day Tokyo), Japan, 1722-3

By the start of the 18th century, Edo â€" capital of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled from the immense castle at the heart of the city â€" was the most populous urban settlement on earth. Almost everything there was made of wood and large fires were routine, especially in the winter months when the air was at its driest and strong winds blew from the north towards the bay.

Reflecting the feudal social order of the day, the primary concern for officials was to protect the castle itself and its military encampment; fires in the rest of the city were viewed not as public health concerns but rather as a problem of social control. As a result, fire protection systems depended on moral exhortation and the threat of punishment.

When major fires did break out, the regime used them as an opportunity to cast such disasters as the product of human failing, not the outcome of poor urban management, and also as a canvas upon which its own disciplinary power could be projected. Between 1722 and 1723, after a series of blazes, the authorities launched a violent crackdown on suspected arsonists in which 101 people, often social outcastes or drifters, were burned at the stake.

Lisbon, 1755

The development of key European cities as hubs of empire and trade led to a shift in how the danger of fire was conceived. With wealth no longer entirely concentrated in the hands of monarchs, and the new bourgeois elites began to view conflagrations a risk to the private accumulation of capital â€" and particularly, to private property.

Merchants and industrialists, mindful of the devastation wrought by the Great Fire of London in 1666 pushed for city-wide fire-protection policies to be thought of as a public good. They were aided in this by new innovations in fire-fighting pioneered by the Dutch polymath Jan ver der Hayden â€" engineer, salesman, artist and fire chief of Amsterdam â€" who watched his city’s town hall burn down when he was a boy and went on to invent a new type of mobile fire engine which featured pioneering water hoses.

It was against this backdrop that on 1 November 1755, a series of violent seismic tremors â€" swiftly followed by a tsunami and then the outbreak of a fire so extensive that it raged for more than a week â€" brought Lisbon, capital of the Portuguese empire, to its knees. Gunpowder shops exploded, churches, palaces and libraries went up in flames, and great clouds of ash fell from the sky, described by an eyewitness as “large showers of fire like hailâ€. Up to 30,000 residents were killed. “I believe so complete a destruction has hardly befallen any place on earth since the overthrow of Sodom and Gomorrah,†reported one survivor.

In the aftermath of the blaze, the entire city centre was demolished and Lisbon was rebuilt according to a radically modernist vision â€" long avenues based around the free movement of people and commerce, buildings regularised in size, structure and decoration â€" that would later be replicated in other great European cities.

Intellectually, the disaster prompted a profound re-evaluation of deeply-held beliefs surrounding god, nature and humankind across the continent and arguably marked the turning point of what came to be known as the Age of Enlightenment; Rousseau, Kant and Voltaire all wrote extensively about what had happened in Lisbon, and used it to develop their philosophical arguments.

San Francisco, 1906

Another fire triggered initially by an earthquake, the blaze that began on 18 April 1906 and raged for three full days across San Francisco destroyed 98% of the city’s most populated blocks and was reported at the time as a great social equaliser â€" a natural disaster which, as one journalist wrote, “did not discriminate between tavern and tabernacle, bank and brothelâ€.

The reality was different. In the early 20th century, San Francisco was a highly segregated collection of ethnic communities marked out by the physical barriers of hills and major streets. Some stood on solid rock; others were resting on landfill for support. “The fires burned â€" block by block, at different rates and times â€" through several residential neighbourhoods,†says Andrea Rees Davies, a former firefighter in the city who is now associate director at the Stanford Humanities Centre. “In this process, the fires, and the city’s responses to them, revealed San Francisco’s social fissures.â€

As the flames spread through the South of Market district, home to poorer San Franciscans, troops moved to guard federal buildings and upper-class homes from looters and fleeing refugees. Soldiers targeted their emergency response towards saving the property of major companies like the Mutual Electric Light Company and the freight sheds of Southern Pacific, while residential blocks succumbed to the blaze.

Meanwhile San Francisco’s Chinatown, the largest Chinese community on the west coast of the US, was left to burn. There was little intervention from the official fire service after a series of dynamite explosions â€" deliberately triggered by firefighters in an ultimately doomed attempt to create a fire break and protect the high-end mansions of Nob Hill.

Lagos, 2002

It was early evening on 27 January 2002 when a small street-market fire in the Ikeja military area in northern Lagos spread to an army storehouse of “high-calibre†bombs, causing an explosion so powerful that it was felt more than 30 miles away. The flaming debris landed in several nearby neighbourhoods; in the ensuing panic, more than 1,000 people are believed to have lost their lives, and more than 20,000 were uprooted from their homes.

After it emerged that orders by city officials for the explosives to be stored somewhere more secure had been ignored, the army’s base commander issued an apology for the accident â€" but that did little to contain the fury of Lagos residents. The conflagration was one of several that ripped through Nigeria’s economic and cultural nerve centre in the 1990s and 2000s, highlighting the iniquities of Nigeria’s economy, in which exports of crude oil had generated vast windfalls for a circle of political operators and business tycoons, but left the vast majority in poverty.

Many of the fires in this period originated in urban spaces that were already the site of political and economic tensions, particularly markets, shantytowns and high-rise buildings â€" the last of which were often government-owned, prompting suspicion that blazes were sometimes started deliberately to hide endemic corruption.

Frustration at the inadequacy of the state’s response to fires has led to firefighters being attacked by some residents who accuse them of being too slow or inefficient. In return, some key high-density areas of the city have effectively been blacklisted by the official fire service.

Buenos Aires, 2004

On 30 December 2004, 3,000 young people gathered for New Year’s Eve celebrations at the Cromañón Republic concert venue to the west of downtown Buenos Aires. During a performance by local rock group Callejeros a pyrotechnic flare was set off which ignited a plastic net hung from the ceiling; fire quickly spread through the rest of the decorations, which were made of wood and Styrofoam, sending molten debris on to the crowd below.

It was later discovered that four of the building’s six exit doors had been chained shut to prevent fans entering without a ticket. Some 194 people died, most from inhaling noxious gases.

At the time of the disaster, Argentina was two decades into its post-dictatorship democracy and supposedly on the way to financial recovery following an economic depression that had devastated millions of lives.

For the best part of the following decade the Cromañón fire and its fallout became entwined with political struggles over contemporary Argentina, and particularly questions of corruption, human rights and broader government failure.

Funeral marches for the dead became protests that involved demonstrators clashing with riot police. The mayor of Buenos Aires was eventually impeached and removed from office as a result of the fire; at a trial in 2008 both the owner of the venue and the manager of Callejeros received jail sentences, as did two city inspectors convicted of dereliction of duty.

Members of the band were acquitted, only to be retried in 2011 and found guilty of murder â€" each receiving 11 years in prison.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

0 Response to "The politics of fire: from Ancient Rome and San Francisco to Grenfell Tower | Cities"

Posting Komentar